NHL player contracts are interesting to look at due to many factors. For one, because they arise from an employer-employee relationship governed mostly by a Collective Bargaining Agreement, they are not “freely” drafted by each team. It makes sense as it creates uniformity across the league and throughout the NHLPA.

But there are some areas where they can be customized. This includes salary and term within the parameters allowed by the CBA. In a previous article we discussed how no-trade and no-movement clauses were one of those areas as well. But there is another term you hear a lot with NHL contracts affecting salary and playing location. Today we take a look at one-way versus two-way contracts with an additional explanation on how waivers relate (or don’t).

The NHL Standard Player Contract

As mentioned above, the NHL Standard Players Contract (SPC) is an already negotiated form included in the CBA as an exhibit. Teams and players can negotiate salary, term, and as mentioned above, restrictions on player movement clauses if such player is eligible. But salary is not a one size fits all.

Obviously, the amount per year can be adjusted and so can bonuses versus salary and term. But because the NHL relies on a farm system and other player loan arrangements for developing players, players on NHL contracts sometimes get another tweak with regards to salary. This is where the terms “one-way” and “two-way” contracts come in.

One-Way Contracts

To oversimplify it, one-way versus two-way contracts deals exclusively with how the player is paid. Specifically, how the player is paid when on a loan from his NHL team. However, one-way versus two-way contracts affect other items too such as salary cap and arbitration awards.

What is a One-Way Contract?

A one-way contract provides that the player will receive a certain salary and that amount will not change whether he is in the NHL or loaned to another team. This includes the AHL, Europe or the ECHL. It is the NHL team that remains responsible for that player’s salary while on loan. With AHL teams typically owned by the NHL team’s ownership group or part of an affiliation agreement with the NHL team, you typically see this question arise in NHL players being sent down to the AHL.

Something to keep in mind is that the AHL team does not pay this salary. There are certain players who sign AHL contracts to which the AHL team is responsible. But such a player cannot go up to the NHL without an NHL level contract. This does not mean that players with one-way contracts cannot be sent down to the AHL. Recently, the Carolina Hurricanes sent Antti Raanta down to the AHL after he cleared waivers (discussed below). But what it does mean is the player earns the same amount whether in the NHL or AHL. This is why players that seem unlikely to play elsewhere typically sign one-way contracts.

One-Way Contracts and the Salary Cap

As far as the salary cap is concerned, one-way contracts are pretty straightforward. Under Section 50.5 of the CBA, in the offseason or during the season when the player is in the NHL, whatever the salary is will generally count against the salary cap. If the player is sent down to the AHL and his salary is the league minimum plus $375,000 or more, the salary over that amount counts against the cap. For example, in 2023-24 the league minimum salary is $775,000. So, if a contract is $2 million on a one-way contract and the player is sent to the AHL, the cap hit would be $850,000. If the salary is under the $375,000 plus league minimum number, it does not.

Two-Way Contracts

Conversely, two-contracts provide that the player will make a certain salary while playing in the NHL and a different, lesser salary, while playing somewhere else on loan. All entry-level contracts are two-way. The difference is that entry-level contracts can slide. So if the contract “slides” the NHL team does not pay the salary for that year. You see this when a player on an ELC goes back and plays in the CHL or in Europe.

Another common two-way contract is when NHL teams sign depth players that may spend time in the AHL. The NHL team remains responsible for the salary but the amount paid while on loan is less. This also applies if players are loaned to the ECHL or Europe.

The one-way versus two-way distinction retains its characteristic if the player is traded. But also a multi-year contract can have some years be two-way and others one-way. In addition, the player will earn pro-rated amounts for the time spent in each league if he goes from the NHL to the AHL or vice versa in one season.

Two-Way Contracts and the Salary Cap

Salary cap calculations for two-way contracts become a little more complicated. The regular season cap hit will be whatever the salary is while the player is playing in the NHL. If the player is sent down to the AHL, the cap hit is generally zero. I say generally because there could be scenarios where there is a cap hit if the player has minimum guaranteed compensation or minor league compensation plus what is known under the CBA as “non-Exhibit 5 performance bonuses” or Exhibit 5 bonuses that are earned that exceed the NHL minimum salary plus $375,000. Exhibit 5 bonuses are bonuses related to entry level deals. It is not common. This is why most just say that two-contracts don’t count against the cap if the player is in the AHL.

In the offseason, the effect on salary cap for two-way contracts depends on NHL games played in the previous year. If a player on a two-way contract played 50 or more NHL games the previous season, his full salary will count against the cap. If the player played 1 to 49 games, it is a reduced number based on a formula. And if the player did not play an NHL game the year before, there is no offseason cap hit.

Waivers

Before the latest CBA, the distinction between a one-way and two-way contract affected whether players had to be put on waivers when sent down to the AHL. But the current CBA, as modified by the MOU in 2020, provides entirely different parameters for requiring waivers. For starters, because a player is on a two-way contract does not necessarily mean they are waiver exempt.

What is Waivers?

Let’s start first with a simple overview of what waivers actually is. Waivers is a process where a player is eligible to be claimed by another NHL team when he is put on them. Usually, this process is required for certain players when teams attempt to send them to the minors. But there are also unconditional waivers that apply when a team buys out or terminates a player’s contract. The latest CBA eliminated re-entry waivers.

Teams have 24 hours to make a claim. If claimed, the player’s remaining contract is assumed by the new team with all of its original characteristics. The order of priority for teams making claims is worst team to best based on the standings. If the player is put on waivers prior to November 1, you look at the standings from the previous year. If after that date, it is the current year’s standings.

Who Must Pass Through Waivers?

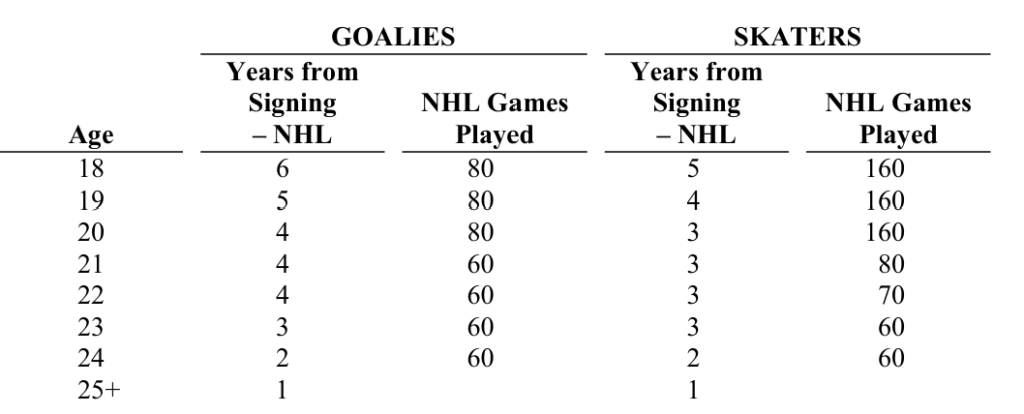

While there are some other specifics on waivers including how trades of players claimed on waivers work, the main question for purposes of this article is who actually has to pass through waivers. The determination depends on four factors. These include: (1) when the player signed his first NHL contract; (2) how many games he has played; (3) how many years since signing the entry level contract he is in the league; and (4) whether he is a player or goalie. The easiest way to see this is to look at the exact chart provided in the NHL’s CBA:

What this means, for example, is if a player signs his entry-level contract at age 19, he will no longer be waiver exempt after the sooner of four seasons OR 160 games played. Of course, it gets even more complicated than this too.

For example, if an 18- or 19-year-old plays 11 NHL games or more, the waiver exemption period is reduced to three years for players and four years for goalies. The next two years for players and three years for goalies count whether the individual plays in the NHL or somewhere else. If a player is 20 or older, the first year he plays a professional game will count as the first year towards exemption. “Professional game” means any NHL, AHL, ECHL or other minor or European league game while the player is on an NHL contract. If a player is 25 or older, the first year he plays in a professional game will be the only year he is exempt from waivers.

So What’s the Relation of One-Way and Two-Way Contracts and Waivers?

Simply put, the difference between a one-way or a two-way contract actually has no affect on waivers. While most players that are exempt from waivers are on two-way contracts, the actual distinction between one-way and two-way has no bearing on waivers. It is simply the entry-level contract age, years in the league, and games played that matter.

The CBA isn’t the easiest document to read. You can see that even in this more narrowly focused topic there are many considerations and requirements. This is why people are paid to analyze it. And why it is such a big deal in negotiating NHL contracts.

Post image attribution: Jenn G, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons