By Alec Roberson

FOR SALE!! Following the death of longtime owner Eugene Melnyk, the Ottawa Senators are up for sale. With many names circling around, Canadian actor Ryan Reyonds recently stated on Jimmy Fallon that he too had interest to potentially purchase the Senators. As a successful Canadian actor, it seems fair, yeah? He has money, he has interest, he currently owns Welsh football club Wrexham A.F.C., so why not? Well, not so fast.

The NHL team purchasing process is one full of multiple hurdles to complete. This comes in the form of economic and logistic hurdles, government/legal hurdles and NHL-imposed hurdles.

What We are Talking About

Before starting I also want to point out that in this article I am really talking about a transaction that involves a willing seller and a willing buyer exchanging money for the team. There are other scenarios that could come with their own set of intricacies such as the death of an owner or bankruptcy resulting in a forced sale or transaction. Keep in mind the Senators are currently owned by Melnyk’s family, so it is not passing from him upon his death at this point. This article does not address those scenarios specifically (but maybe for another day….).

While this article will not cover every aspect of the NHL team purchase transaction due to the complexity, I broke this article into three parts. In Part I I will cover some of the economic and logistic considerations. Most of these considerations start before the parties sign the purchase/sale contract. Part II will cover non-NHL related legal and “closing” considerations. Then Part III will focus on NHL league considerations and rules. Parts II and III focus mostly on considerations happening after the sale is under contract but before it closes. For example, it is common for NHL approval to be a contingency for an executed contract.

With that said, let’s dive into Part I and the economic and logistical conditions necessary for the sale of an NHL franchise to make it across the finish line.

Economic Considerations

As Reynolds stated in his Jimmy Fallon appearance, it costs a lot of money to purchase an NHL team. Like, a lot a lot. Usually, investment groups or billionaires are the one’s making such purchases.

Some examples of owners include Jeremy Jacobs, who Forbes listed as the 271st richest person in the United States, of the Boston Bruins, Tom Dundon, owner of Dundon Capital Partners and a major investor and Chairman of Topgolf, of the Carolina Hurricanes, and the late Eugene Melnyk, founder of Biovail Corporation which at one time was one of Canada’s largest publicly traded pharmaceutical company, of the Ottawa Senators. Mario Lemieux was a majority owner of the Penguins until recently which was a more unusual situation. Long story short, the Penguins owed him so much in back salary he used that to purchase the team out of bankruptcy. That is a very unique situation but as we previously discussed in an article on avenues players explore after hockey, you never know. Regardless, you need a lot of money.

The Shiny Toys….

As stated above, these teams are not cheap. We are talking hundreds of millions of dollars on average for a given team. It is a fairly interesting dynamic when it comes to economics as the supply of teams is extremely limited. There are 32 teams. Out of those 32 it is not often that a team is even for sale. This drives the price up. However, due to the cost associated with these teams, demand is limited to only those with deep pockets (or with friends with deep pockets). This is the luxury purchasing business for sure.

And buying a team is not always profitable. This isn’t really like investing money with the goal of making money. It is more like a shiny toy for those that can afford it. But most of these toys are not cash cows minus a few teams such as the NY Rangers and Toronto Maple Leafs.

Valuation of the Senators

So how expensive are NHL teams? Forbes valued the Senators at $525 million as of December 2021. Sportico has its value for the Senators at $655 million. Reynolds’ net worth is estimated at around $150 million. So even for someone like Ryan Reyonds, it’s a steep price. This is why if he is able to successfully obtain such a shiny toy, it will likely come with others’ involvement.

Logistical and Structural Considerations

Moving past the strictly economics, there are various ways this purchase could happen. Keep in mind that usually holding companies with layers of corporations or other entities actually own each NHL team. So, when I say buying the team what I really mean is the ownership of the holding company that controls the team unless otherwise stated.

One Entity Owner Per Team

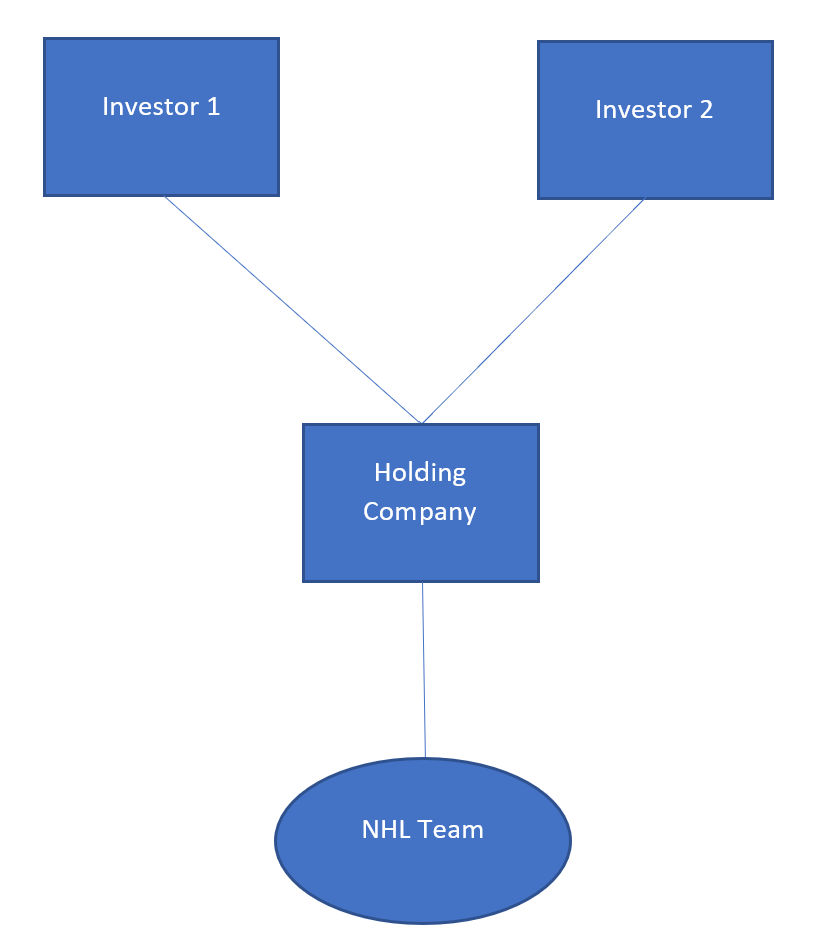

One option is that each interested party collectively forms an entity (think a corporation, LLC, etc.) to which they each have an interest based on their investment and responsibility. That entity then purchases the team. One team, one owner. Multiple people or entities own the entity which then owns the team. In this case the single entity is probably the holding company. If there is a single owner, that owner may own the team him or herself, even if through another entity. This structure could look like this:

Multiple Entities/Owners Per Team

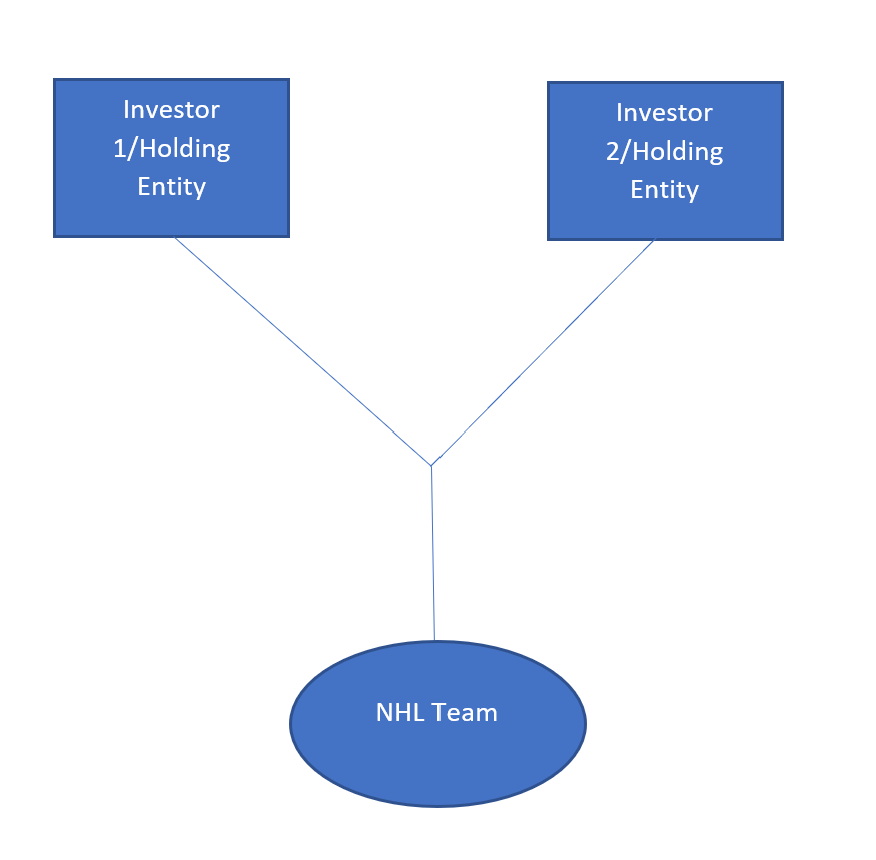

Alternatively, each owner could buy a portion of the team individually. In this scenario the holding company might not be the only direct owner of the team. Again, the owners split the team up based on investment and maybe responsibility but instead of one team one owner, it’s one team multiple owners. Generally speaking, this structure depends on who is involved and has control. This structure could look more like this:

Keep in mind that these diagrams are probably the simplest form of these ownership structures. In reality there are likely more investors involved and additional tiers of ownership. No matter the specifics, when there is a group involved with the goal of purchasing the team, this is known as a consortium. This is probably the most common ownership of teams. Even if the most “publicly known” owner is the majority owner, there are likely minority owners helping out.

Money and Control

Money and control are usually the deciding considerations for how to structure the purchase. So let’s take Reynolds for example. Say he wants to actually control the Senators as an owner but doesn’t have the funding to buy it on his own. So he gets another or other investors to jump on board.

Does he maintain 51% ownership so he can have control? Well, that comes at a higher price. Maybe that is worth it to him and he can leverage part of his purchase through lending versus equity. Or maybe he doesn’t want so much debt involved so he gives up control but stays on as a minority investor. Of course, it is also possible that no one is a majority owner (i.e. no one has greater than 50%). In that case there could be more decisions by committee when it comes to control but each party has less of a financial investment.

The other option is to set it up where one party has more responsibility while the other or others are more fiscally responsible. The easiest example of this is a limited partnership where you have a general partner who leads the partnership and the limited partner or partners are on board as “silent” partners, most likely providing funding.

Tax, Privacy and Liability

Once the purchaser or purchasers determine how they want to structure the purchase under money and control considerations, then there are tax, privacy and liability considerations. Each entity comes with its own set of tax requirements. Likewise, the entity’s type and domestication can affect the liability and privacy of the individual owners. Think of how many corporations incorporate in Delaware, there’s a reason. I don’t want to get too far into these pieces as they are largely legal aspects (coming in Part II) but they largely affect how the purchase is structured. It is important to think about under this lense.

The Buying Structure Becomes Another Layer of Negotiation

One other piece to think about is how settling how you want to structure and finance the purchase leads to a whole additional set of negotiations outside of the purchase of the team itself. So if a buyer is interested but needs the help of others, now there is another layer of potential negotiations with the other potential buyers involved. Who is contributing what, who has control, etc. etc. And if there are multiple potential buyers jockeying to get the team, they have to move fast. They wouldn’t want to get stuck negotiating percent ownership of the team or purchasing entity while another buyer swoops in and gets the team. There are ways to alleviate this but nevertheless, it makes these transactions very complicated.

At the end of the day, determining and structuring such bids is a hurdle. Maybe not the most challenging hurdle but one, nonetheless.

Conclusion

The sale of an NHL team, at its core, is not too different from any sale of a major private organization. One or a few owners sell to one or a few buyers (versus the sale of a publicly traded corporation). The economic considerations are high due to valuation and limited supply. The logistical considerations are complex because it is not a one size fits all scenario and the size of the transaction is so large. If you make this type of purchase, you want it to be right. This isn’t buying something that can just be thrown away without severe loss.

From an economic standpoint for the NHL, maybe Reynolds buying the team would be a good thing. While the NHL can’t just give Reynolds the team, nor can it alleviate all the burdens associated with purchasing a team, it may be wise for it to try its best to move the process along to allow Reynolds to become an owner. A major Canadian born movie star as an owner, that might be a jolt to the NHL it could use to increase ratings and popularity. Will it happen? Who knows.

Stay tuned as we dive into some of the non-NHL legal considerations involved in closing the sale of a team in Part II.

Post image attribution: By: Gage Skidmore from Peoria, AZ, United States of America, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons